Photo Essay

Sri Lanka’s “New Wave” Murals

Sri Lankans, amid the rumored beginnings of a global pandemic and a highly polarized political climate, took to walls across the country to “beautify” their neighborhoods.

The exact origin of Sri Lanka’s “new wave” murals is unknown. The works of art started to appear en masse around the end of 2019, as Gotabaya Rajapaksa became president in a landslide victory. Sri Lankans, amid the rumored beginnings of a global pandemic and a highly polarized political climate, took to walls across the country to “beautify” their neighborhoods.

The media attributed the work to a wave of youthful enthusiasm during a period of national and local pride, and touted it as a neutral attempt to beautify urban spaces. But the works reveal underlying truths about identity and politics in contemporary Sri Lanka. Most are ideologically loaded, and many reinforce Sinhalese origin myths. Problematically, some murals show public support for known extremists. The valorizing of individuals accused of war crimes and propagators of hate speech is common.

A small minority of murals representing cosmopolitan ideas are found in towns with multiethnic populations. In towns where national minorities form the local majority, murals carefully assert their respective ethnic and historical identities without displaying aggression. Pastoral scenes and other nonviolent depictions of identity are common in these spaces, with some exceptions such as a few murals found in the city of Jaffna.

Many murals reflect aggressive, masculine values. Masculinity and progress, development, and identity appear to be strongly correlated in the public imagination. Ravana is a common figure who appears in both majoritarian and minority contexts, seen as a shared origin myth in Sri Lanka.

The painting of murals is an ancient tradition in Sri Lanka. The medium is closely associated with Buddhist and Hindu traditions, which hold painting as the highest form of art. Highly skilled examples can be found in temples across the country, and the murals in Sigirya are among the country’s most famous cultural sites.

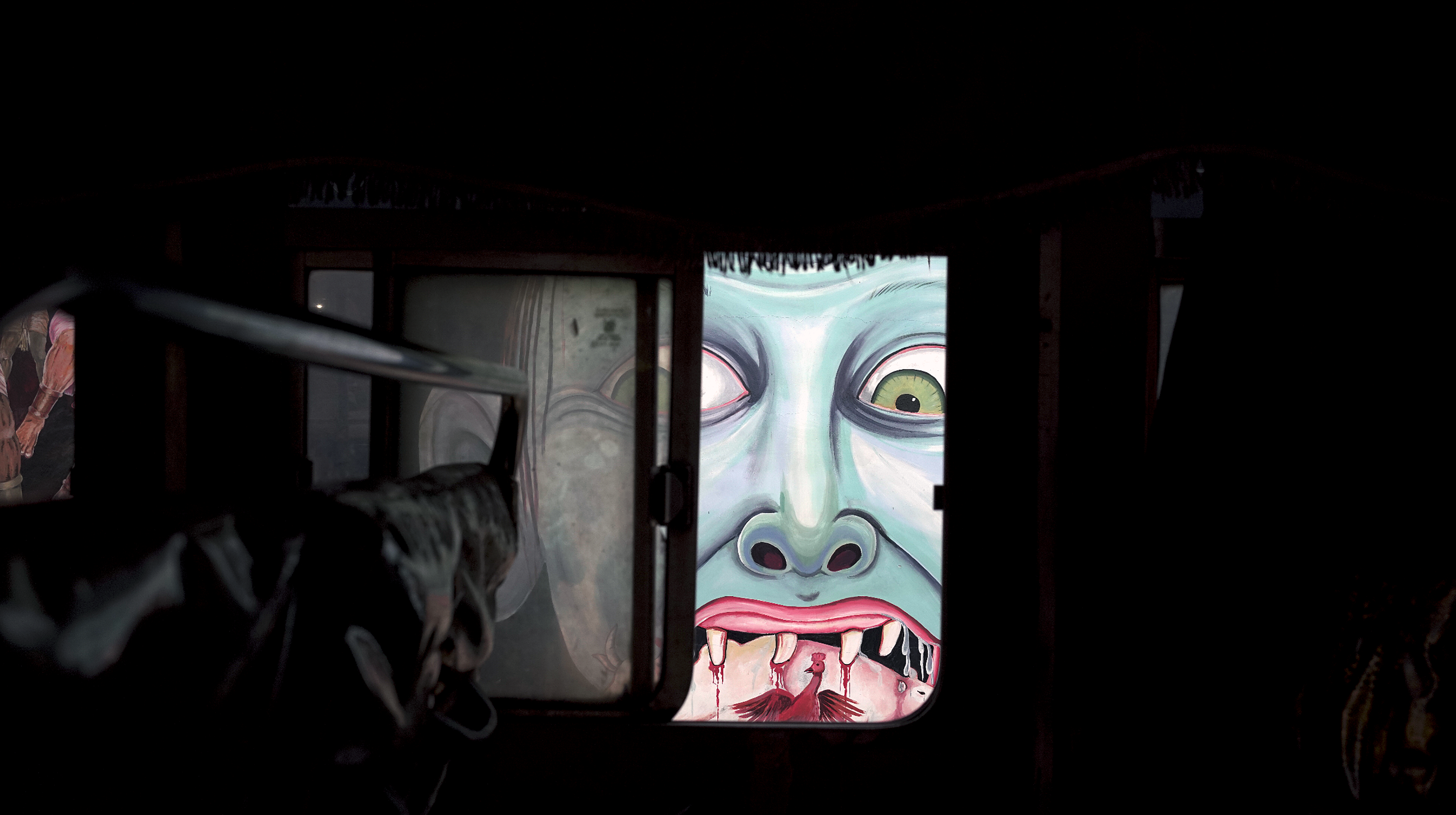

New works also depict western pop culture and tackle issues such as environmental damage and the dangers of social media. Others depict scenes drawn from imaginary landscapes.

As progress fails to actualize the aspirations embedded in their airbrushed surfaces, the optimism that inspired these murals fades. Fewer new murals are appearing, and those that remain have become repositories for dreams that fade as their paint fades or their surfaces are vandalized, bulldozed, or hidden.

A mural on the walls of the Public Market in Trincomalee depicts scenes from an imaginary science fiction/fantasy landscape. (Photo: The Asia Foundation/Abdul Halik Azeez)

A mural in Medawachchiya shows the arrival of Buddhism in Sri Lanka via the monk Mihindu, son of Indian king Ashokha, who is depicted at the Mihintale rock teaching the king of Sri Lanka. (Photo: The Asia Foundation/Abdul Halik Azeez)

This mural in Anuradhapura depicts the arrival of Vijaya, an exiled Indian warrior prince, mythically regarded as the progenitor of the Sinhalese race. (Photo: The Asia Foundation/Abdul Halik Azeez)

Buddhist, Hindu, Muslim, and Christian religious leaders stand together in this large mural in Hatton. (Photo: The Asia Foundation/Abdul Halik Azeez)

A mural in a public bus stand in Medawachchiya depicts the Kaaba, in Mecca, an important place of worship for Muslims. (Photo: The Asia Foundation/Abdul Halik Azeez)

A mural in Jaffna depicts a touching moment between a boy and a cow, an animal sacred to Hindus. (Photo: The Asia Foundation/Abdul Halik Azeez)

A mural in Jaffna depicts a Tamil prince or king. (Photo: The Asia Foundation/Abdul Halik Azeez)

Ravana, a prehistoric Sri Lankan king said to have his own flying machine, floats above the ground in a mural in Dambulla. (Photo: The Asia Foundation/Abdul Halik Azeez)

A mural in Medawachchiya reproduces an ancient mural drawn on the Sigiriya rock. True to form, poetry graffiti in the form of a phone number is scrawled on its surface. (Photo: The Asia Foundation/Abdul Halik Azeez)

Gollum, Medawachchiya. (Photo: The Asia Foundation/Abdul Halik Azeez)

Back

Back