Photo Essay

Maratabat: A Double-Edged Sword

The Maranao believe that the mental construct of maratabat, or family honor, has been misunderstood.

The Maranao, indigenous peoples of Mindanao, uphold the deeply-held cultural value of maratabat, or family honor. It is pivotal to their individual, family, and community identity, however some believe the concept is often misunderstood and misused.

Maratabat is heavily borne by all family members and is linked with everyday conduct as well as key life events. A family receives more honor and will express pride when a son or daughter receives a college diploma. The inverse is also true, one would rather die than tarnish the family name. Perceived slights or insults to a family member may result in a cycle of revenge between clans.

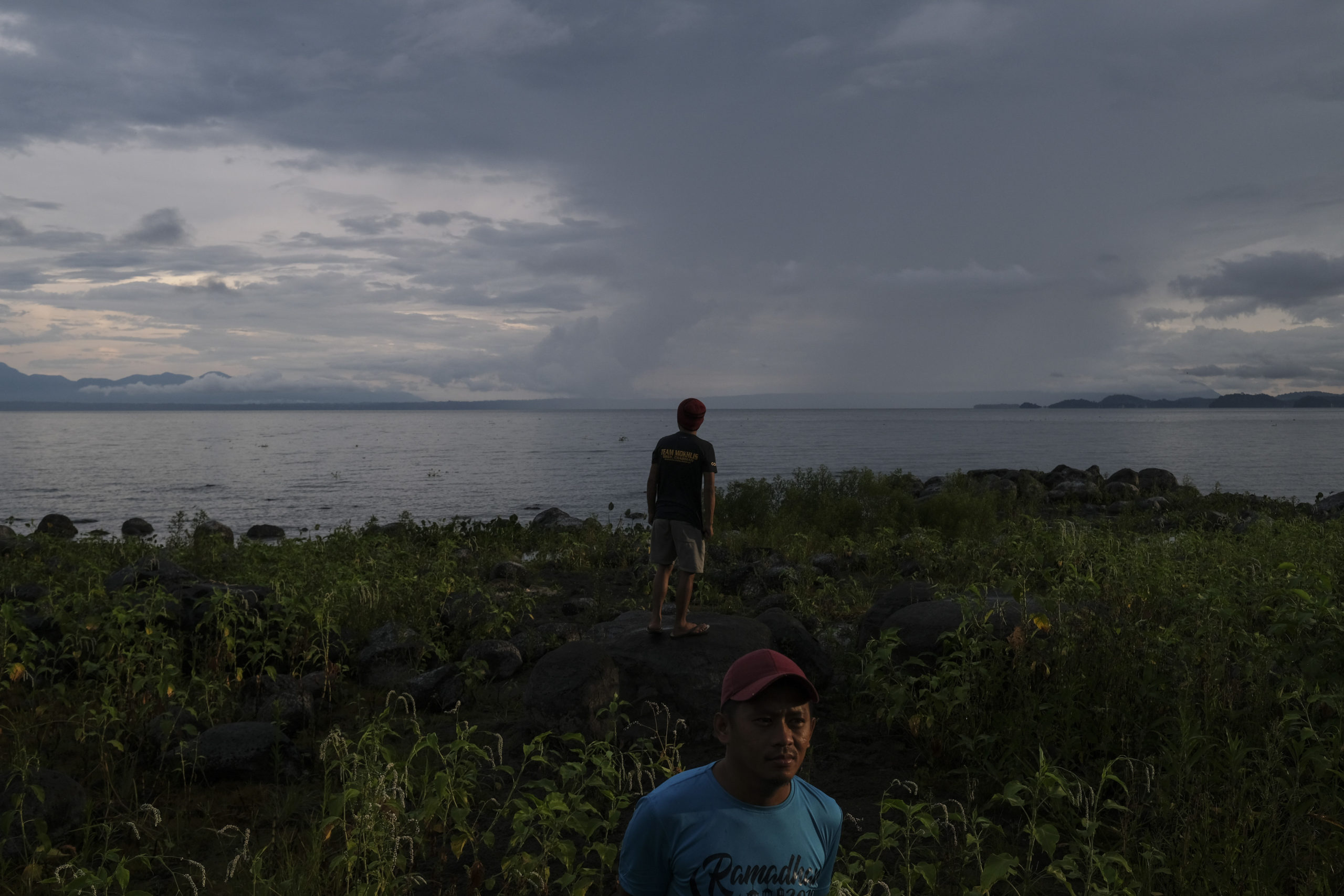

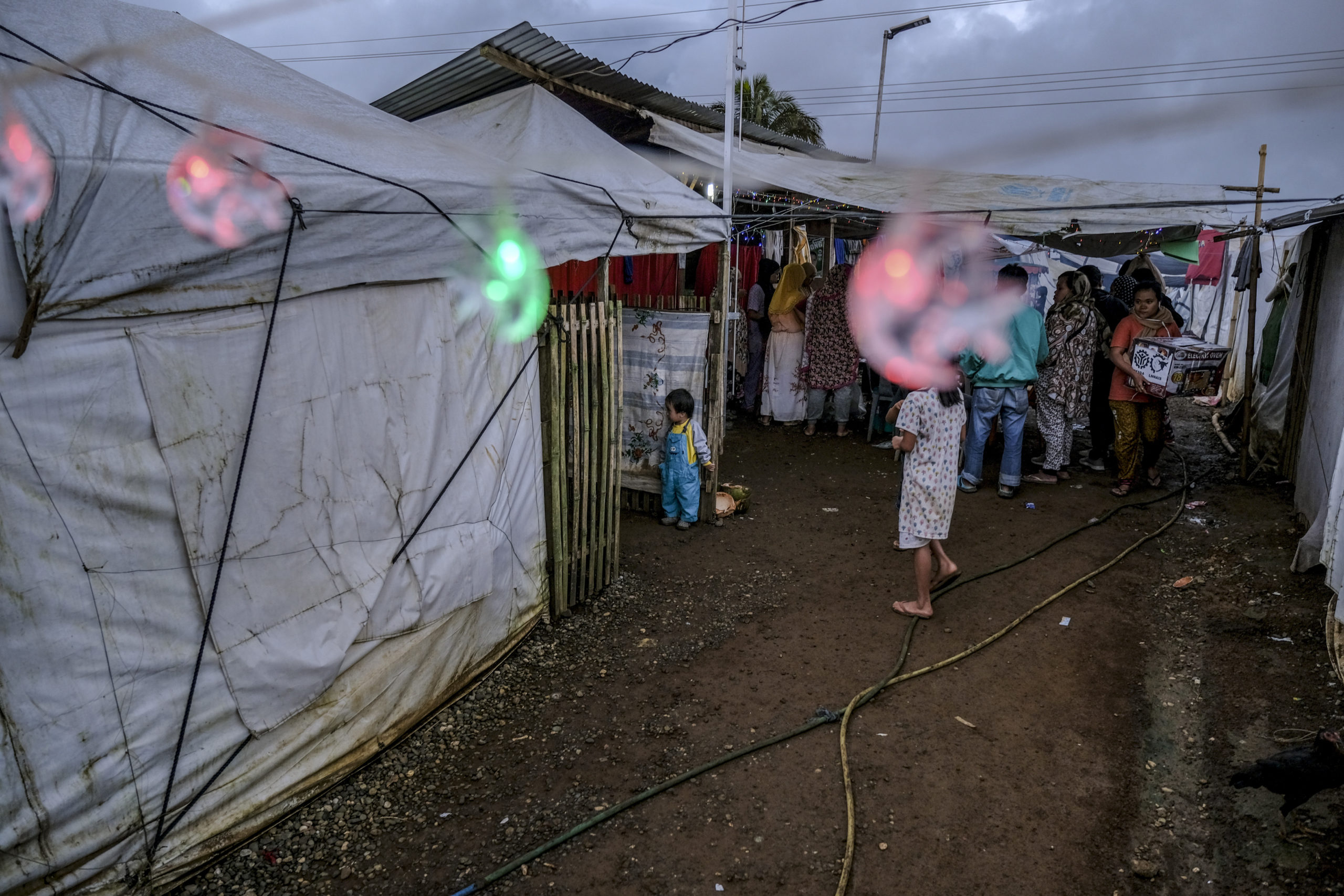

In May 2017, the ISIS-backed Maute Group attacked the Islamic city of Marawi, attempting to establish a Caliphate in Southeast Asia. Once known for its bustling trade and commercial centers, the city was ravaged by five months of intense fighting. The formerly affluent Maranao way of life was shattered, and many were left dispossessed and homeless, forced to rely on relatives and emergency shelters.

During and after the event, maratabat was invoked, even abused, to justify retaliation and to motivate further violence. Despite ongoing cycles of revenge, the practice of helping one another—especially among relatives and clan members—still abounds.

In this uncertain time, the Maranao still hold their heads high as they rebuild and reclaim their land, no matter what they might find. For this is the only way to regain family honor and dignity: to live in the land that their forefathers fought for.

Residents spend an afternoon by Lake Lanao, near ground zero in Marawi City, Lanao del Sur. (Photo: The Asia Foundation/Veejay Villafranca)

Remnants of heavy shelling are seen along the streets of downtown Marawi. (Photo: The Asia Foundation/Veejay Villafranca)

A girl sits among glamourous gowns in a rental shop in downtown Marawi. (Photo: The Asia Foundation/Veejay Villafranca)

Students of Mindanao State University cheer during a program on the Marawi campus at the start of the 2019 school year. (Photo: The Asia Foundation/Veejay Villafranca)

Maranao students attend classes in bullet-ridden classrooms near “ground zero” in downtown Marawi, where the intense clash between government forces and ISIS-inspired fighters took place. (Photo: The Asia Foundation/Veejay Villafranca)

Schoolchildren participate in sports activities outside a makeshift classroom at a temporary site in Lanao del Sur.(Photo: The Asia Foundation/Veejay Villafranca)

A child with a disability sits in a wheelchair outside the transitional shelter for displaced residents of Marawi. (Photo: The Asia Foundation/Veejay Villafranca)

Dilapidated tents serve as temporary shelters for the hundreds of families displaced by the 2017 conflict in Marawi. (Photo: The Asia Foundation/Veejay Villafranca)

Remnants of a heavily damaged downtown area, once a bustling business district, still stand at ground zero in Marawi. (Photo: The Asia Foundation/Veejay Villafranca)

Signs of heavy shelling and explosions mark the 84-year-old St. Mary’s Cathedral in Marawi City, where the ISIS-inspired Maute Group desecrated and destroyed religious icons at the start of their siege in May 2017. (Photo: The Asia Foundation/Veejay Villafranca)

The Sining Kambayoka Ensemble practices their routine at Mindanao State University in Marawi for a May 2019 performance. (Photo: The Asia Foundation/Veejay Villafranca)

Schoolchildren attend classes at a newly built school in a transitional shelter in Marawi. (Photo: The Asia Foundation/Veejay Villafranca)

Schoolchildren share a light moment before they start class in a makeshift classroom at a temporary site in Lanao del Sur. (Photo: The Asia Foundation/Veejay Villafranca)

Back

Back